Draft Four: Never enough time

On how time-poverty is messing with our head.

Treat your weekend like a vacation.

It’s advice I heard on a podcast about how to make the most of your time. I listened to it on my Saturday morning run, an 8K through two parks close to my apartment. The run was a preamble to getting coffee and banana bread, then starting to write this letter, the first after a two week break.

It resonated partly because I did treat (most) of my August weekend days like vacation: I ran, I read, I played Football Manager (hello from 2036), did some cleaning & some chores, watched shows, listened to music, had ice cream with friends, did more reading, did some editing.

The advice comes from a time and happiness researcher trying to wrestle with one of our fallacies: most of us complain of having not enough time, and dream of days when we can do nothing. But study after study has shown that we’re not happy when we have too much going on, but we’re also not happy when we have nothing going on.

The pressure to do everything is as bad as the pressure to do nothing.

Which is the point of the weekend as vacation nudge – do whatever you have in mind (including catching up on some work), but sprinkle in the things that bring you joy. I’m still surprised at how little I need to feel at peace, and it’s mostly the list above. We can actually cut it down to coffee, reading, food, and conversation, and I’d be fine.

*

There have been a few things on my mind recently – the joy of process in creativity, making hard choices in the pursuit of excellence, how storytelling highjacks our negativity-oriented brains, the trivialization of confessional writing – but I’m still coming back to time, which I also wrote about in a mid-year review.

If you passed your early to mid-thirties (hello, you are safe here) you already know that much of what you thought earlier about time and time management was wrong, especially the idea of not having enough of it. Now we know better to not confuse busyness with choice. We understand how much we screw over our future selves when we commit to things way down the line thinking we’ll have more bandwidth. We know time management is not a solution to things we can’t control. And we’re mature enough to understand calendars are not oppressive mechanisms if used correctly.

And still…

*

I write this from the standpoint of a journalist, and our relationship with time is pretty odd: it’s never enough, rubbing up against deadline is like a high that’s terribly bad for you, but having too much time is too much freedom, and who wants that?!

Some of us grew up working on deadline. I remember being an assistant city editor during my master’s program and the adrenaline rushing through my body from 8 to 10pm when the last stories had to be delivered to the copy desk. The senior editors had taken care of the most important stories before taking off, but there was always the late city council meeting, some evening accident, a game, or an event that needed covering. The reporter would rush into the newsroom all crazed at 9pm going “Oh God, oh God, oh God, how the hell am I going to get this out in an hour?” We always did get it out, and I never had much doubt. That deadline was not a threat, but a friend: do the best you can by 10pm. We’ll go again tomorrow.

That means I still have plenty of muscle memory of this. When I see someone worrying about how they’re going to write an email when they only have an hour for it, my instinct is to say: “What a blessing!” As I write this, I have a 60-minute timer on my phone counting down to a break. But I also scheduled it to get my ass in the chair and start writing. Terribly unsatisfying pro tip: The only way to write something in an hour is to sit down and start typing.

I intellectually know all this. I feel it every time I do something that I didn’t think I had time for. I sometimes do exercises where I tell people to write for five minutes. One of the learnings is always how much they actually covered in such a short period of time.

But that doesn’t mean it isn’t hard as hell sometimes.

One reason I took a break the last two weeks is because I didn’t think muscle memory would carry me through. It seemed too much.

*

Two things I want to explore here:

- Task-switching is such a high cost that it eats up seemingly available hours.

- Time-poverty, or the feeling you are rushing, makes you a worse person.

The first is something I’ve written and thought a lot about in the context of freelancing. I am really overloaded these days, and while the volume itself is or seems doable, the cost of switching from one project to the next is so tiring, that I am unable to use my time to deliver quality work for all projects. And there are five or six or seven of them right now.

Dude, you may say, who made you say yes to so many things?

I know the theory: when someone asks you to do something or join a project, you should really try a version of the following. Ask yourself if you would do love to do that thing if it was tomorrow. Only say “yes” is the answer is an emphatic “hell yeah!” Or ask yourself if you’d have time for that request the day it was made. If the answer is “no”, you won’t have time for it next month either.

Following this theory is harder. I’m getting better, but I’m not there yet.

There’s another aspect to this. Freelancing is an uncertain state. I had a cash flow meltdown in May and June. There was money due to come in, but for a few weeks I was so low on cash I had to borrow from friends and family. Then July came, and so did the money for the work I did. Then, in a panic to not repeat May and June, I said yes a few too many times, and from now until November I’ll be paying the price for that fear. The less fun thing is that payment for jobs I then did in July has been unreasonably delayed (choose your partners wisely, fam), so I’m almost back where I was three months ago. Which makes the panicked side of me say: “That’s why we said yes to everything!”

You can see how this becomes a vicious cycle: you’re low on resources, you say “yes” to too many things to avoid facing that shortage again, then boom, you’re suddenly overwhelmed. Then you say too many “no”s while dreaming of peace, and a shortage is once again possible. Repeat.

Some of you reading are probably better stewards – both of your money and your temperament – but I know so many people, especially journalists and artists and NGO workers that live like this. I actually had coffee or beer with them in the past few weeks, and this is a lot of what we talked about. They’ve been living like this for so long that they’ve stopped questioning whether another way is possible.

Six concurrent projects, all necessary because otherwise the money would not add up, but none of them benefiting from one’s best work.

This is a recipe for burnout, mediocre work, and unhappiness.

I don’t believe it’s solely within our own individual powers to change this significantly. The real struggle would be to change this systemically – which in journalism and cultural projects and NGOs would mean foregoing relationships with sponsors/donors who keep insisting on “frugality” and “efficiency”, which translate as “you can cover the costs, but no paying yourself”. It would mean asking for more (more money, more support, more resources), or less (less deliverables, less bureaucracy, less monitoring).

Another observation: the LinkedIn stock advice about timeboxing things, being upfront with partners and clients about available hours, being disciplined about when stuff is done is all great unless you work with creatives that don’t neatly fit into your grid.

For example: This week I set time aside for editing about 10 drafts of stories for a live journalism show I’m working on (to be announced this coming week). The deadlines were set together with the writers, the brief was clear, yet none delivered on deadline. So instead of editing 10 stories, I am editing two. The others I’ll have to find time for by moving other work around, which is harder when you are a freelancer or a cog in someone else’s project. I can’t tell the conferences I’ll be speaking at in late September that I’d rather not join calls and prep meetings because some editing has come up (that wasn’t supposed to).

Again, nothing new, but things are worth repeating.

Very few journalists I have worked with delivered on deadline. The problem is that many still deliver mediocre work even a week later (although they specifically said they need the extra week to raise the level of quality). It’s not because they are not good at what they do, it’s mostly because they are themselves trapped in the cycle above and are lying to themselves about it. I’d venture to say that those that historically have delivered on deadline (give or take 1-2 days) almost always delivered better work because their life or their own systems were set up for that.

So yes, we are all masters of self-deception about what we can do in the time we have.

But we are also poorly compensated for the work, or don’t get enough validation for it.

So we take on extra things, many extra things, making the equilibrium more fragile, and increasing the complexity in the system. The amount of stuff you can’t control grows exponentially. If a new project with five collaborators enters your life that’s not an addition of one. That’s an addition of multiple relationships, with different needs and challenges.

You are slowly becoming more strained, and more stressed.

Task-switching becomes more costly (energetically).

Procrastination becomes a form of defense.

Shit doesn’t get done.

So your good habits are under threat, as you replace your morning run with catching up on email, and your weekend-as-vacation with editing something you should have edited on Thursday, but didn’t get it.

*

I’ve struggled with forms of the above all my life and will continue to do so.

Generally, it’s not a me-problem or a you-problem, at least not in the creative industries of Eastern Europe. It’s also a money thing, a structure thing, a respect for discipline thing. It’s an ecosystem-wide problem and of course you can try to do it differently – I often do, emphasizing structure and clarity and transparency. Just beware that there is a cost for that, as well. People don’t want our solutions, especially since what they use delivers results. Sure, it breaks them, but our default is to pick certainty, even if it’s painful, over the anxiety of uncertainty, even if it promises better outcomes.

*

I also want to address how time-poverty, or the feeling you are rushing through everything, is making you a worse person. I feel that about myself: when I’m overwhelmed and stressed and worried about too many things, I don’t only neglect myself, but others as well. I talk with my family less often, I don’t reach out to my friends and colleagues, and I have less empathy for others.

I was recently chatting with a friend about what we do when we run into a person lying on the sidewalk, something that’s becoming a common sight in downtown Bucharest. I stop and check and call emergency services, my friend said. I wish I was as good a person every time. But I’m not.

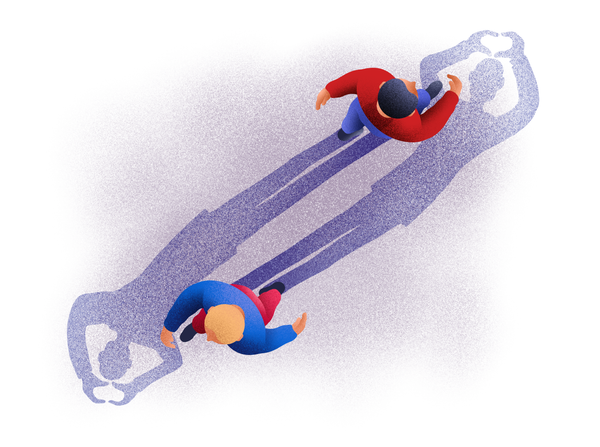

I also know how much this is not just about my own moral compass, but about how clear my head is. Let me share one my favorite things: it’s a pretty famous experiment about helping others that shows how this brain fog sets in. Princeton seminary students are told they must deliver a lecture about caring for others. But the lecture they must deliver is across campus. Some are told they have enough time to get there. Others are told they really need to rush, or they’ll be late.

On their way to the lecture all participants come across a fallen stranger – a study confederate who looks like they are really suffering. More than half of those that are not rushing, stop to help. Of those that are rushing, barely anyone stops; many don’t even notice the person struggling.

We are not the people we think we are when our heads are flooded with worry about all the shit we have to do.

(It gets worse, mind you. There was a similar experiment done with soccer fans. When people were primed to think of identifying with their favorite team, they were more likely to help a fallen stranger in their team’s shirt than if they wore the shirt of a rival. There is an upside too – when primed to think about the sport as a unifying force, fans help supporters of rival teams, too. But not people who are not soccer fans, unfortunately.).

Just remember this: perception of personal time-poverty is making us more self-absorbed, and unable to extend much empathy to others, which is necessary for good collaboration, especially when stressful times will occur in projects – as they always do.

A closing note: doom scrolling, or revenge scrolling are the worst habits you can tack onto time-poverty. I did have a couple of nights like that this summer and the next morning felt like a bad hangover. Here’s an extra tidbit on the risks, from the Hidden Brain newsletter:

Researchers found that “digital switching,”— that thing you do when you toggle between videos and fast forward through them — can backfire. In a series of experiments, people who engaged in digital switching felt more bored than people who stuck with watching a single video. It’s the paradox of our times: We have access to an endless amount of content to keep us engaged, yet the more of it we consume, the less engaged we feel.

*

Knowing something doesn’t mean you’ll do it. Which is why I’m revisiting the lessons above. The new one from this year is mostly about the ups and downs of available cash when freelancing (versus the steadiness of a paycheck, even when modest), and how that fear and scarcity affects decisions: in my case, it makes me break many of my own hard-learned rules about how many things to get involved in at once.

The lesson I always love to re-learn is about how action beats procrastination. The ass in chair advice for writing holds a ton of truth. The draft of this letter clocked in at 2.300 words, and it took me two hours (about 20-25 of those were water and bathroom breaks). That doesn’t mean they are the best words, the only words, the sharpest words. But they exist, and I have at least another hour to rewrite1. That’s plenty of time.

SIDE DISHES:

1. There is also a story to be told about “passion”, and its dangers. Spoiler: take breaks.

2. Here’s a book from a writer who takes ass in chair seriously. Autoportrait by Jesse Ball is a stunning autobiographical exercise that is the result of one day of writing (on a foldable keyboard connected to a phone!) I love this bit: “The advice I most often give my students is to contradict themselves. Please, I say, please please please contradict yourself”.

3. Why is loneliness so hard to cure? Because even if connection is what we are after, we can’t solely achieve it the way we did 50 or 100 years ago – we need to find ways that match the present we live in.

4. A solid list of 75 nice things you can do for yourself from Ann Friedman. Here’s three I loved: “Take quiet weeks after social weeks”, “Don’t hold your pee for anyone! Go when you need to go.”, “Stop reading the news like it’s your job.”

Another good advice is “write hot, edit cold”. This often means you take time away from what you wrote so you can come back to it and sharpen it. (And trim it). The final length of this letter is longer than the draft, so coolness was not achieved. Will try again next week. ↩