Draft Four: The Doorway Effect

Finding some light in the darkness.

I’ll start with a snapshot from earlier today (Saturday): I’m in the middle of my living room, I’ve rotated all the furniture, I don’t like the result, and I have a feeling my life isn’t quite what it should be. Almost instantaneously, another thought follows: that’s a tad dramatic.

A few hours later, my one-year-old apartment in my almost 100-years-old building is in what my father called “winter mode”. This means I moved my couch closer to the radiator, and my desk back out on the enclosed balcony, which is no longer a hothouse, as it felt from early May to late September. There is a warm light overhead, and I’m eating the Hamburg grapes I bought at the market, on the walk home from the mall. I try to avoid the mall at all costs (at the cost at skipping a bunch of movies), but I went to get trekking boots for an environmental journalism bootcamp I’m co-teaching in a national reserve alongside with my former colleagues Anca Iosif and Sorana Stănescu. (The environmental part will be taught by a dozen experts – we’re there for the journalism part.)

On the way back, I got street food – a CovriLuca –, which locals already know as a staple: a hot dog baked into a bun sprinkled with poppy seeds that sells for 1 Euro. And then, for dessert, one of those fancy French Revolution eclairs (mango today, thanks) that costs a whopping 5 Euros. The grapes were 3 Euros for 1 kilo.

If this feels like nothing special, it’s because it is.

It was just of those days that doesn’t leave a mark on the world, but that I need every once in a while, to recharge. It wasn’t “doing nothing” – moving furniture and cleaning isn’t nothing –, but it was “doing something else” than I had been for the past few weekends: editing, making Keynotes presentations, catching up on emails, traveling etc.

Now comes the harder part: what followed the above is the writing of this letter. Technically work. What happened for some of the time I was moving stuff around and cleaning was that I was listening to podcasts on the latest Romanian political dramas, the rise of authoritarianism, the Electoral College of the US, whether Donald Trump is a fascist, and other gloomy stuff about the world. And while it worried me, it also energized me. (Maybe this is what’s weird about us journalists. We hear sad stories and go “oh, please tell me more”.)

*

Yesterday I had coffee with a community facilitator I greatly admire, and she was recounting a conversation she had in a once blooming spa-town with elder locals who had seen it become a ruin, and recently arrived younger folks who saw the potential. The older people said: “We need the sadness and hopelessness”. The younger people said: “Please don’t take our hope away”. What they were wrestling with wasn’t specific urban development policies, but a personal relationship to a place: the memories of something that once shined clashed with the aspirations that the place might once again be beautiful.

My friend teared up recounting this exchange – something heavy was said in that room, two generations asking for nothing else but to be seen in their sadness, and in their joyous aspirations respectively. For that one brief moment, they made sense to each other. Will they ever build together? That’s a whole different question.

In one of the podcasts I listened to today, they discussed current US demographics: young women are leaning more progressive, increasingly moving to the left after a decade that saw the rise of the #metoo movement, and then Roe v. Wade be overturned, ending the constitutional right to abortion. For them, the built-in discrimination in many systems is something to fight for. Young men, on the other hand, especially those without a college degree, are voting for Trump and are frustrated because their economic prospects suck, and so they can’t fulfil their traditional roles as providers. (Also, some have been blackpilled, but that’s a different story). These two groups rarely overlap anymore – very few of those interviewed said their partner had different political beliefs, and those that did said it created a lot of “awkwardness”.

This is what’s difficult about how we live today: leaving room for one’s feelings without having to agree with their choice of handling them. Young men feeling they won’t make it, won’t be able to buy a home, won’t be able to support a family is a tragic reality (and it’s not just in the US). We have to take that in, and somehow provide solutions that are alternatives to voting for autocrats.

I’ll say something about Trump here, and that’s because we’re less than 10 days from the US elections: I buy the very coherent argument that has been made over and over now that a second Trump presidency is more worrisome than the first. And that’s because Trump would be coming into office not just as his unhinged self, saying whatever comes to mind, but because now he plans to be surrounded by loyalists who’ll do his bidding, which will include using the state apparatus to go after his perceived enemies – from former staffers and appointees, to the media, to who knows whom. This not a man interested in governing – this is a man solely interested in power, who gets a kick out of using it discretionarily. America has not yet become an autocracy, but it might well become one. If it didn’t in Trump’s first term that’s mostly because civil servants, boring bureaucrats, generals (some of whom later called Trump “a fascist” because of how he desires to wield power), and others, tripped him up. Even went as far as trick him into thinking they were doing his bidding, and then didn’t.

This is so hard to process: you have a man running a country like the US that has the patience of a toddler, that people tiptoe around and trick, and promise to do something for “later”, hoping he’ll get bored of his recent whims – such as shooting protesters in the feet, missiles into Mexico, playing music instead of answering questions. That’s a despot. (Don’t know why this just reminded me of the evil lord in Ottessa Moshfegh’s creepy Lapvona).

*

So that’s what I’m doing – cleaning my house, thinking about the US elections, and how they will reverberate in the Romanian ones coming up next month. (Right now, all we have is huge slate of presidential candidates all pitching themselves to the conservative majority and telling various stories about how they’ll make us great again.)

So basically basking in the bleakness that already exists in the world. But is there any light?

On Friday night I went to see my former colleague Ana, alongside whom I’ve done some of my best work as an editor. She is now one of the volunteers of the Museum of Abandonment,

a digital museum that recovers and digitizes the archive and memory of institutionalization. It is a private project of an NGO which, unlike the state, is trying to unearth this past and become a virtual space for dialog between the “invisible community of abandoned children” and the general public. Dozens of student volunteers plus historians, anthropologists and communication experts are working on a digital map of all the orphanages, with information and pictures for each one.

I’m quoting from the last piece Ana and I worked on together for DoR. It was about the blessing and curse of international adoptions following the reveal to the world in the 1990s of “Ceaușescu’s children”, generations of kids raised in abusive institutions, treated so badly that they became the basis of most of what we know about early childhood trauma.

The Museum and other entities are piecing together the legacy of those institutions, and slowly coming to understand and grasp that we might be dealing with the lives of maybe half a million children that were impacted. Some of those died as young as 3 or 4 or 5 years old. By the hundreds in some of these institutions, many of whom had entire graveyards in the back of the buildings.

The stories the Museum has unearthed are terrible. This is a national trauma the state should recognize (and arguably pay reparations for), but nothing has been done so far. But in all that darkness, the staff also found institutions that treated children differently. The one they are currently building an interactive digital exhibit around was in Zau de Câmpie, in a castle just over an hour from where I grew up.

The girls there were still abandoned, still orphaned, but had food, had care, had books read to them, played together. Which means that what happened to them was both a result of state policies, but also of people that held on to their humanity and didn’t turn into brutes just because that behavior was condoned or tacitly encouraged by the regime.

One of the Museum staffers told a story of being in Zau and running into a woman who grew up there. She now lived in England and was visiting with her children. She wanted them to see where she came from, and when they were exploring through the dark basement of the now abandoned former orphanage, she told them: “Don’t worry, nothing bad ever happened here”.

*

I don’t know what my point is other than there are horrors all around us, and there is also grace. That the world out there is loud and going to hell, but that every now and then you can shut yourself off from it, and move furniture around, and take it in from afar. You don’t disengage, you don’t turn away, but you control the exposure, you allow some light in, you see the sadness and you see the hope at the same time.

There is hope after all, at least in how Rebecca Solnit defines it, and I’ve quoted her before: “Hope just means another world might be possible, not promised, not guaranteed. Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope.”

*

A friend asked me yesterday for a video I sent her about positive affirmations. Yes, I know, I struggle with these, too. But what was special about this particular video was that it tied the idea of positive affirmations (saying something good about yourself) to the doorway effect. If you ever found yourself going from one room to another and suddenly forgetting why, that’s the doorway effect. What happens when we move through spaces is that we go through “event boundaries”, which help the brain compartmentalize. (This also makes memories from one room feel less relevant in the next).

The legendary swimmer Michael Phelps is among the ones who said he used to say positive affirmations as he moved through doorways, taking advantage of the brain’s programming. New space, new you. Of course this doesn’t work like magic, but it shows we’re operating in continuums: from one room to another, from darkness to light, from sadness to hope.

Nothing major happened today. It just started off poorly, and somehow, one doorway after another, it ends better. The world is not better, our politics is not better, my country isn’t better, but at least better versions of possible exist.

That’s my hope for you today, too.

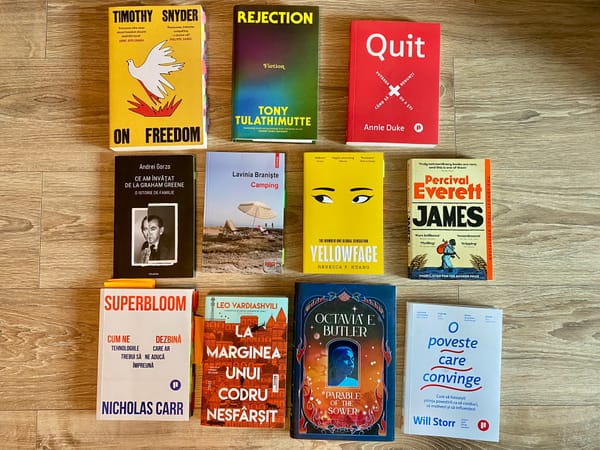

SIDE DISHES:

- This 1-minute Instagram recap of storytelling show in Sibiu. It was emotional, intense, cathartic, and fun. And we had wine at the end. If you’re in Bucharest on Tuesday, November 12, come see this version – it’ll have journalism, essays, theater, stand up, and music. Tickets are 75 lei (15 Euros).

- Here’s some of the podcasts I listened to while cleaning my house – a conversation with the makers of Autocracy in America. And the first piece from the latest On the Media about using the word “fascism” as it regards Donald Trump. (There’s also this stunning Ezra Klein essay about why Trump is unfit for office).

- One of my favorite newsletters from my region is Peter Erdely’s – he tackles media funding, and in his latest he explains the fraught dynamic between content creators and newsrooms.

- This beautiful song turned 20 this year.

PS: This newsletter will probably reach 3.000 subscribers this coming week, which make me feel grateful, and scared at the same time. In all honesty, I am considering dedicating more time to it in 2025, so if you want to help me do that, you can pledge to financially back it – payment will happened only when and if I start charging for it. The option should appear below or in the upper right hand corner on this page.