Draft Four: We launched a podcast

And here are some things we’ve learned.

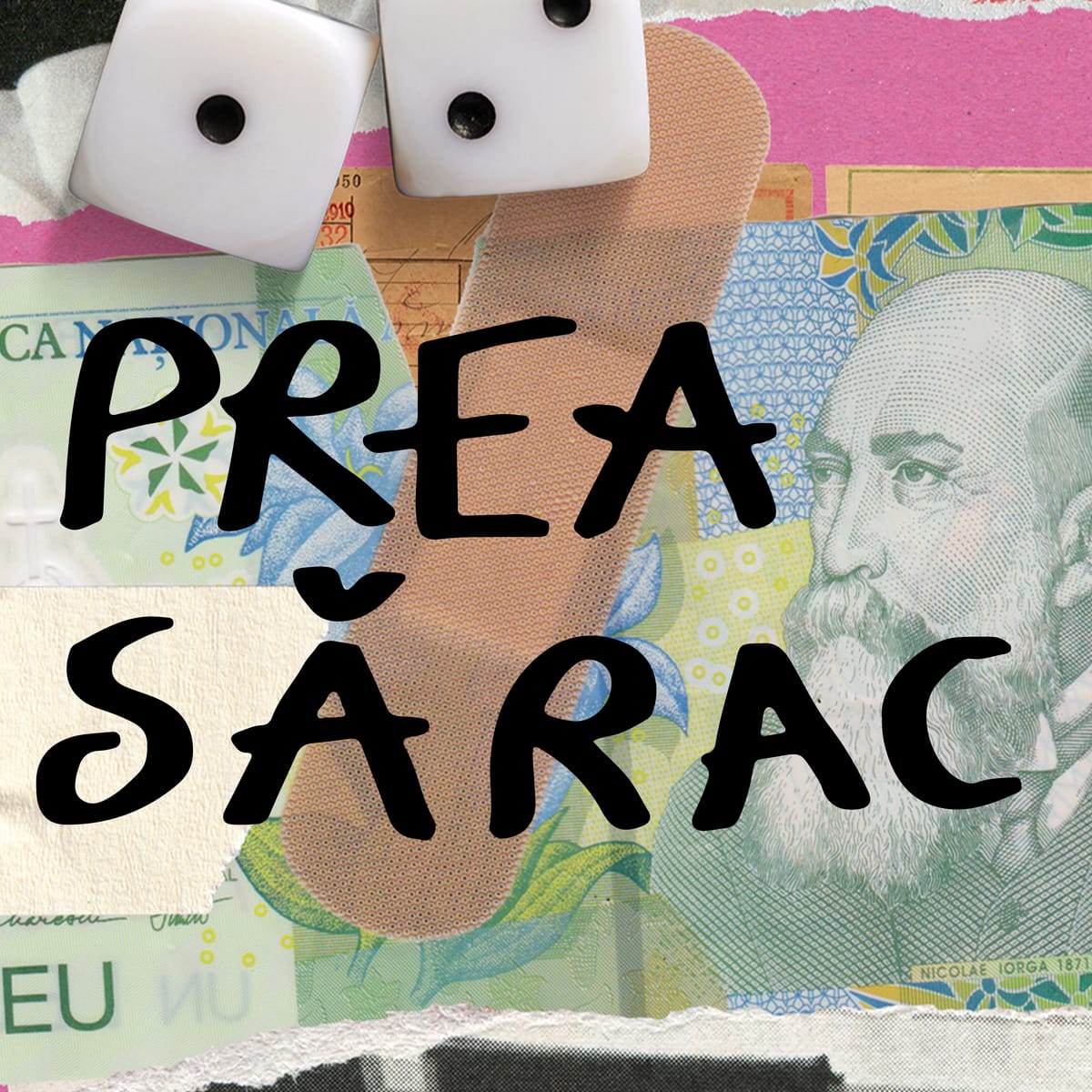

TL;DR. If you want to skip all this and listen to the first episode of Prea Sărac, it’s on YouTube, Apple Podcasts, Spotify or whichever other platform you prefer. Thank you!

*

In July 2023 we hosted some 20 young people in our office at Media DoR, the NGO running our projects. They were mostly students and young grads – journalism, arts, communications etc. We wanted to encourage them to see possibilities in a rather bleak media environment, so we split them into five teams for a day-dreaming exercise. With no constraints, no adult supervision, and little guidance from a brief, what would they make?

One group looked into climate coverage, one at politics, one played a rogue squad of Gen Zs inside a large media brand, and so on. When we re-grouped a few hours later, a common theme emerged: daily life was becoming increasingly more expensive. Rent in Bucharest was punishing, starting salaries didn’t keep up with inflation, and you can forget about discretionary spending.

We’re too poor to choose the jobs we want to do, was the bitter joke of the afternoon. We even thought it might make for an interesting project: the felt reality that many are too poor to do meaningful things. Time poor. Energy poor. Hope poor. And, of course, money poor.

*

Over the years, Romanian journalism did its best to find ways to cover the issue of poverty, which is a complicated and sometimes unhelpful umbrella term. We often failed. Even today some of us fall into the trap of talking about “people on welfare” as if they are a problem, or as if they are a drain on the country’s resources. After 35 years of recoiling from anything to the left because it sounded too close to the communism we wanted to demolish, we instinctively embraced a position that was, if not against the social safety net of the state, then at least skeptical of it.

As a society we championed rugged individualism and the privatization of the social space as sure paths to the good life. In this landscape, the supposedly social-democrat party was anything but. Occasionally backing social policy simply because it worked as elections-bait, it enabled the fracturing of institutions, graft, and furthered a lack of solidarity. The liberals or the more recent reformists did no better.

Neither did journalists or activists. We did poverty porn, fundraised of the backs of people – often kids – in severe deprivation, didn’t take time to understand what austerity measures mean and so on. Some of that changed in the past 15 years as a new generation of media and activists came on the scene: stories about what daily life is like for people in poverty came out, the voices diversified, the push against corporate overreach and austerity strengthened.

In my world, some reported from a distance, some matched reporting with solutions-seeking, others chose activism. We tried our best at DoR to show both the individuals, as well as the systems behind them: how being a social worker in the forgotten North-East was a calling, because it wasn’t a role that anyone rewarded; how fixing inequalities in schools can’t solely be done with well-meaning teachers backed by NGOs; how precarity fuels gender violence, and so on.

In 2017, we launched an audio narrative series expanding one of these stories: Satul Mădălinei. It told the story of a young mother who asked for money on subway platforms in Bucharest, commuting from outside the city to do so. There was no work for her in the village where she lived, plagued by intergenerational poverty, bureaucratic violence, and a dearth of services. Fate would bring her face to face with do-gooders who thought they could help – through charity, and individual acts of kindness. They did. To some extent. That was the tragedy: you can’t fight that kind of deprivation through charity – you have to change systems, laws, mindsets, and the following wicked problem.

Romania is a social state (on paper) that is terrible at delivering its supposed free services: education, healthcare etc. But we need to protect it and work to improve it, so we don’t turn to private healthcare or private education as the solutions, because they’re not.

*

Back to that day with the students. Afterwards I bought a domain name – preasarac.ro. (Too Poor). It was a reminder of that day, but also a sign of something.

Fast-forward into the never-ending 2024 elections and you have a Romania with staggering inflation, chart-topping inequality, seething with anger. And it’s less the Mădălinas’ anger that was showing – it was people in relative poverty or at risk of social exclusion, or people who cosplayed a middle-class lifestyle while propped up by crippling debt, a health crisis away from losing everything. People for whom the word “poverty” brings up stigma and shame, and who thought it had nothing to do with them – the poor were people who had nothing.

If you had something, even if that something was far from an indicator of a decent standard of living, you were OK. If you had a roof, you were OK. If you were working and you couldn’t cover all your expenses, you were still OK.

Until you weren’t. Or until you realized you weren’t, and maybe that’s not the kind of life we want for so many of the people around us. (Almost a third based on stats.)

This is a conversation I’ve been having off and on since mid-2022 with my former colleague Andreea Vîlcu, who was my student a decade ago, and then we worked together. In our final issue she wrote about growing up with debt, parents losing what they thought was that OK life, spiraling into a reality where power was cut because bills weren’t paid, where gambling seemed like an out, and where personal resilience, not solidarity, was the escape. Andreea worked in bars and malls to get herself through university, and pawned many objects, multiple times, to make rent.

This precarity brought shame. It wasn’t absolute poverty or severe deprivation – depending on the measure you look at. It was the invisible kind, the people you pass by on the street, whose life you know nothing about but who are far from benefitting from the much touted macro-economic growth of modern-day Romania.

Andreea remained preoccupied by people like herself: Who are we? What does this precarity do to us? Why does it create so much anger and shame? Why does it make me want to turn against the state for taxing my salary, when maybe I should turn against corporations for exploiting us? What’s up with this reality, how has it changed in a period of austerity, and what can we do about it?

This sounded like a journey. Then I remembered we might have a vehicle to take that journey with: Prea Sărac.

Play the first episode.

Prea Sărac is the name of the podcast we launched on Wednesday. We’ve been working on it for a few months, and much of it is, still, a work in progress. Especially defining the multiple layers of deprivation that exist. Severe deprivation is clear: not having access to basic living conditions, such as running water, heat, or nutritious food. The rich seem simple, too, right? They are probably the people on the other side of the ledger that has brought the average income in Bucharest to 7.000 lei. But what about the in-between? And how many layers are there in this in-between – the ones at risk of social exclusion, the working poor, the fragile supposed middle class, an actually stable middle class? And how can we talk about them?

Here are some early lessons we’ve learned. They might be more useful to journalists, but maybe not:

1. You need resources and a team. And (probably) they won’t suffice.

To lower the pressure to do a podcast, we decided to call it “an experiment”. Andreea hadn’t done a podcast, but really wanted to, especially after listening to Classy, which explores how class shows up. We didn’t want to do it without resources – journalists and NGO-workers burn themselves out in droves doing too much, with too little. We gave what we still had in the NGO to this project – that’s about 20.000 euros, to bring together a part-time team of 4 people, plus 2 others helping out, and a bunch of collaborators.

Getting the right people matters, and the most important was arguably Ana Ciobanu, the reporter behind Satul Mădălinei, because she knows how audio narrative is reported, edited, and mixed.

That was in late May. By the end of the year, people in the core team will have made close to 5.000 euros, which sounds extravagant on paper but divided over 7 months of work, it comes under the national average salary per month, far from matching Bucharest costs. Yes, better than many others have it. Sufficient? Doesn’t seem to be so, since everyone has a few other jobs – which cuts deep into the time we could spend together.

2. Plan but be flexible.

I still have an index card next to my desk that says: “Plan the hell out of it. Hold it lightly.” It helps, because going into the unknown pretending to know what will come out is a recipe for disaster. From the outset we said this was an experiment – whatever happened happened. If we put out an episode, great. If we ended up doing nothing, great. If we realize this is the beginning of something that could be more complex and larger, great.

It needed to be what would emerge organically.

What did emerge was the skeleton of a limited six-part series, where we’d feature the intimate stories of a few people that struggled or continue to struggle with precarity or the shame and fear of it, alongside the journey of a host trying to put together what that says about her, and what it can teach us about tackling the systems that enable them: unchecked capitalism, flawed bureaucracies, misguided politicians, and a lack of empathy.

3. Have at least the semblance of a strategy.

We knew from the get-go that we picked the worst form in which to deliver stories: narrative audio in a media landscape where podcasting has become synonymous with video interviews. Add to that the fight for attention in an information landscape where everyone is shouting. So, because we wanted people to listen to it, we decided to try and build an audience before it came out, ideally try to reach as wide a demographic as possible, including people who don’t engage with this topic or avoid it, even though they would have gone through – or maybe actually go through – similar issues. Here, it helped we had Nicole’s ease on social media, collabs we made with friends, a visual identity created by Oana Barbonie, original music by Mihai Pîrvan, Tudor Pană’s video editing help etc. This is complicated for journalists everywhere today: trying to make something attractive, because otherwise it risks going unnoticed. The reason not to do it is that it simplifies the ideas and people make up their minds before anything exists. The reason to do it is that it will reach people who needed this who otherwise wouldn’t have known. Both are proving true.

4. Involve the public.

As we started working, we sent out a form asking people about their experiences with money and precarity. More than 400 replied, and their concerns revolved around the necessity of working multiple jobs, as well as the persistent fear of financial instability due to illness, job loss, or unexpected expenses. Many recounted having or fearing debts, rents, or loans, and a pervasive sentiment around “the shame of not having” – often rooted in past family struggles like bankruptcy or growing up in poverty. (You can still fill it out!) It informed the themes we tackled, the people we interviewed, and also showed us that covering the topic for real – and at length – could take years if we kept going.

5. Get the right partners.

To be able to cover the costs I mentioned above we still needed to fundraise an extra 10.000 euros at a minimum. Given the amount, we thought we should try companies – but no banks, credit institutions or the likes. And no gambling, tobacco or pharma, which we’ve always avoided. That cut the potential, but we still thought we had a chance. Then we heard back: this sounds sad, and we can’t back that. If you manifest poverty, you’ll attract it. Why do you think we’re the target audience; just because we do discounts??? Not necessarily surprising, but dispiriting.

Thankfully our colleagues at Recorder, arguably Romania’s most successful independent media, came through and supported us with a grant. For them, it’s part of a larger mission to expand their reach to colleagues who do good work, but need help making it visible. We are forever grateful.

6. Reception

As I write this on Saturday afternoon, October 18, more than 10.000 people have at least hit play on either the YouTube version, or the podcast app version (Spotify, Apple Podcasts etc.) The vast majority of the feedback is overwhelming and touching: people sharing stories of their own struggles (past or present) and shame, understanding they are part of a larger story in a country that still ranks towards the bottom of many EU standard of living rankings.

And, of course, there is backlash or pushback from people who believe our choice to highlight relative poverty and its facets detracts from the attention that must be paid to severe deprivation, and criticism of punitive austerity measures. These are not mutually exclusive in my mind, and these folks are right – there must be more journalism (or activism for that matter) about the latter. Some criticism, while harsh and sometimes delivered without having heard the story – means well. It also opens important conversations about the boundaries between telling a story and activism, about who is entitled to tell whose story, about what meaning and measurements we ascribe to words like “privilege” etc. A small part of the criticism is simply spiteful and hurtful, which is today’s online discourse.

7. Next steps

Some of these are clear: we have a few episodes drafted or outlined that we want to put out by the end the year. I hope many more people hear these stories and find something in it for them: if not a mirror, then something to think about when we ponder whether Romanians’ access to prosperity hasn’t been unfairly distributed.

Otherwise, there is years’ worth of stories to tell: about severe deprivation, about what is a fragile middle class in Romania, about our traumatic relationship with money, about how vice industries and extreme right politicians benefit from all of these, and much more.

I hope you give it a chance. Also consider supporting it with a one-time donation if it speaks to you. And, if you don’t speak Romanian, YouTube will helpfully translate the subtitles into a language of your choice.